Book

Notes on Complexity by Theise

I finished reading Notes on Complexity by Neil Theise this morning. It is a quick read just under 200 pages, and I think would be best thought of as a quick overview of very deep topics on complexity theory and winding all the way to consciousness.

I found it immediately engaging because my own reading on Buddhism has left me intrigued by how well it connects to some very big scientific concepts. I’ve also been listening and meditating using Sam Harris’ Waking Up which frequently visits topics around “the observer” and consciousness.

What I took from Theise’s notes were parallels between Relativity and Quantum Mechanics, and Formal Logic and Metaphysics.

From this idealist view, then, the universe as a whole, including each of our bodies, brains, and minds, is nothing but a manifestation arising from the depths of an underlying Consciousness. Space, time, matter, and energy, the quantum foam, all the structures that emerge from these, have no inherent existence but are simply experiences within that Consciousness. Idealism affirms, in the grandest way possible, that the brain doesn’t make consciousness; it is Consciousness that makes the universe, out of which, after billions of years, our brains have emerged to be the most complex structure we have yet discovered. And thus, if everything is only a subjective experience of the big-C Consciousness, then the hard problem of what creates subjective experience ceases to be a problem. There is nothing in the universe that is not the subjective experience of Consciousness.

This call out about artificial intelligence was interesting as well. Most people approach this question as consciousness derives from enough intelligence. But considering consciousness and intelligence as independent properties suggests a very different outcome.

It heralds an approach to how we can navigate from the strangeness of quantum realms up into the normal-seeming, classical realms of everyday experience. It also suggests that algorithmically programmed computers can produce artificial intelligence, but not true consciousness, because consciousness is not just an emergent property of complex programming. If one wants to make “real” artificial intelligence, then computers need to become transducers of awareness, as brains are, a matter that seems beyond complex programming.

This isn’t a field that I have the depth to explore in detail, but I find the connections interesting and enjoy the exploration.

The Boy Who Would Be King

Tyler and I read The Boy Who Would Be King together tonight. It is a good book, and the story and points are made well. The illustrations are also well done.

What books are on my office book shelf?

I recently shared a selfie from my office and a friend emailed me to ask what books I had on the book shelf behind me. I tend to keep multiple copies of a set of books in my office and I happily give them to anyone that wants a copy. The books that I keep in there change slowly over time, but this is what I’m stocking today and why. These are in no particular order. You can see all of these on my technology management section on Bookshop.org.

Measure What Matters by John Doerr

This is a great introduction to OKR’s. Wether you adopt OKR’s formally or informally, it is worth reading to understand the mechanics and how various organizations have used this framework.

An Elegant Puzzle by Will Larson

This is a thorough and complete writeup of many topics related to managing and leading technology teams. Well written and useful information. As an added bonus, it’s an incredibly well designed and produced book.

Inspired by Marty Cagan

Insightful book that covers on the critical aspects of creating great products. Covers all of the aspects, not just building the software.

Checklist Manifesto by Atul Gawande

Wonderful book that highlights the power of checklists. Highlights what makes a good checklist and why. Must read.

Getting Things Done by David Allen

I’ve been using the GTD method for over a decade and routinely recommend it to people as a way to manage not just their work, but their whole life.

Agile Software Development with Scrum by Schwaber and Beedle

I have probably bought over 100 copies of this book over the years. I still reference it for those that want to learn about Agile and Scrum. I don’t remember how I was introduced to this book, but I’m very thankful I read it early on.

The New Leaders 100 Day Action Plan by George B. Bradt, Jayme A. Check, John A. Lawler

This book was recommended to me by a friend when I joined SPS Commerce. It served as a great roadmap and absolutely helped me be more successful as I started as a new leader. I give this book to every Director and up that we hire!

Trillion Dollar Coach by Eric Schmidt, Jonathan Rosenberg, and Alan Eagle

The story of Bill Campbell who coached some of the biggest technology companies in the world. This book provides some great insight into the role of a coach in business. By reading it, I think you can be a better coach too.

Accelerate by Nicole Forsgren, Jez Humble, and Gene Kim

Great overview of how a modern technology organization should run and deliver value.

Thinking in Systems by Donella Meadows

System thinking is one of the most critical things for growing and changing companies to keep in mind. As managers you are often designing systems that people and processes operate in and around. This is a good entry level discussion of the topic, and will make you a better designer of those systems.

Radical Candor by Kim Scott

I enjoyed this book for it’s approach to candid conversations in the workplace and how to approach them.

Leadership Pipeline by Stephen Drotter, Jim Noel, and Ram Charan

Good book on thinking about leadership development from entry level manager to functional leader and enterprise leader. I like how this book is structured and the critical questions it asks the reader to consider.

The Goal: A Business Graphic Novel based on The Goal by Eliyahu M. Goldratt with Jeff Cox, adapted by Dwight Jon Zimmerman and Dean Motter

The Goal is a classic book, and the concepts in it are one that many technology leaders may not have front of mind. The graphic novel is a fun way to make it even more approachable.

The Change Monster by Jeanie Daniel Duck

This book is a simple way to think about organizational change, and how to lead your organizations through it. I found this book when I was doing a lot of mergers and it was helpful to think about the process and the emotions associated with it.

The Cognitive Style of Powerpoint: Pitching Out Corrupts Within by Edward R. Tufte

I share this with people who want more information on why I’m so suspect of bullet lists and “PowerPoint thinking.”

Started reading Digital Minimalism by Cal Newport tonight. 📚

Book: When Breath Becomes Air

I’ve had “When Breath Becomes Air” sitting at our cabin for a while, but decided to pick it up and read it on winter break. The book is a memoir by Paul Kalanithi told in two parts. The first part is his path through medical school and becoming a neurosurgeon, being close to serious illnesses, and dealing with death as a Doctor. The second part is after his cancer diagnosis with stage IV lung cancer, which causes his death within 18 months.

There were two things that struck a chord in me while reading this.

I kept thinking back to Being Mortal by Atul Gawande. I’m sure it was in part because Kalanithi, like Gawande, is a Doctor. The first part of the book had many references to the Doctor’s perspective when diagnosing a patient with a terminal illness. This book did too. Being Mortal is a very different book, and one that I highly recommend reading, but this touched on similar topics with a more personal perspective.

The other thing about this book was more personal. It reminded me in so many ways of the path of my friend David Hussman, who passed away earlier this year. He had the same diagnosis, stage IV lung cancer. I’m pretty sure he even had the same EGFR mutation and received similar treatments. Similar to Kalanithi, he did remarkably well for a long while after getting treatment. Enough that you could kind of forget a bit. But the cancer is just held back a bit. I was wishing I would have read this book when I got it, as it would have given me some deeper perspective when talking with David.

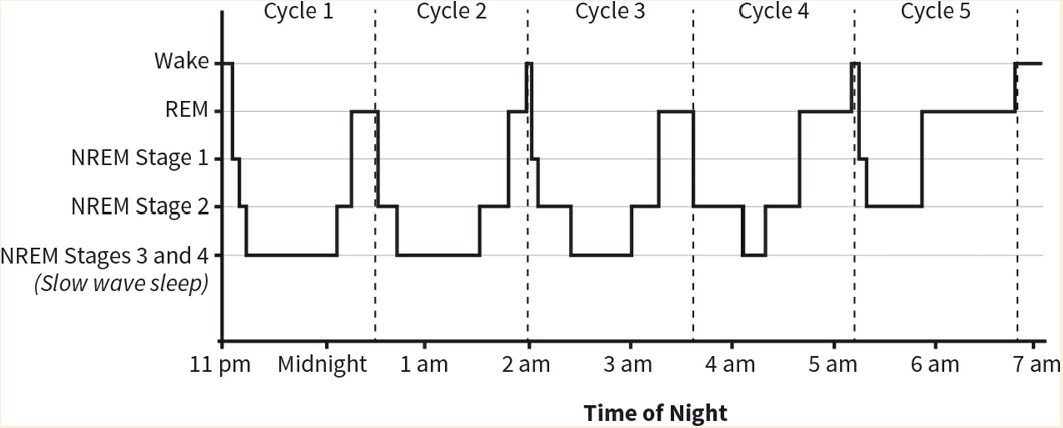

This graph is in Why We Sleep and is super interesting. Only just getting started on this read and already learning a lot.

Book: Why Buddhism Is True

I recently finished reading Why Buddhism is True: The Science and Philosophy of Meditation and Enlightenment by Robert Wright and enjoyed it very much.

I appreciated how Wright connected ancient Buddhist concepts to modern psychology. His deconstruction of complex topics like essence and nothingness are well done and allow Western readers to connect to them easier. I would highly recommend this book if you are curious about meditation and the overall approach to mindfulness.

I’m trying something new, and sharing my highlighted passages from the book.

1. Taking the Red Pill

Page 8

Natural selection doesn’t “want” us to be happy, after all; it just “wants” us to be productive, in its narrow sense of productive. And the way to make us productive is to make the anticipation of pleasure very strong but the pleasure itself not very long-lasting.

Page 12

To live mindfully is to pay attention to, to be “mindful of” what’s happening in the here and now and to experience it in a clear, direct way, unclouded by various mental obfuscations. Stop and smell the roses.

Page 14

Buddhism offers an explicit diagnosis of the problem and a cure. And the cure, when it works, brings not just happiness but clarity of vision: the actual truth about things, or at least something way, way closer to that than our everyday view of them.

2. Paradoxes of Meditation

Page 18

Technologies of distraction have made attention deficits more common. And there’s something about the modern environment — something technological or cultural or political or all of the above — that seems conducive to harsh judgment and ready rage.

Page 21

This is something that can happen again and again via meditation: accepting, even embracing, an unpleasant feeling can give you a critical distance from it that winds up diminishing the unpleasantness.

3. When Are Feelings Illusions?

Page 29

Feelings are designed to encode judgments about things in our environment.

Page 33

This is a reminder that natural selection didn’t design your mind to see the world clearly; it designed your mind to have perceptions and beliefs that would help take care of your genes.

Page 40

cognitive-behavioral therapy is very much in the spirit of mindfulness meditation. Both in some sense question the validity of feelings. It’s just that with cognitive-behavioral therapy, the questioning is more literal.

4. Bliss, Ecstasy, and More Important Reasons to Meditate

Page 57

Noticing that your mind is wandering doesn’t seem like a very profound insight; and in fact it isn’t one, notwithstanding my teacher’s kind insistence on giving it a standing ovation. But it’s not without significance. What I was saying in that session with my teacher was that I — that is, my “self,” the thing I had thought was in control — don’t readily control the most fundamental aspect of my mental life: what I’m thinking about.

5. The Alleged Nonexistence of Your Self

Page 62

But, he notes, our bodies do lead to affliction, and we can’t magically change that by saying “May my form be thus.” So form — the stuff the human body is made of — isn’t really under our control. Therefore, says the Buddha, it must be the case that “form is not-self.” We are not our bodies.

Page 63

So two of the properties commonly associated with a self—control and persistence through time — are found to be absent, not evident in any of the five components that seem to constitute human beings.

Page 71

But once I followed that logic — quit seeing these things I couldn’t control as part of my self — I was liberated from them and, in a certain sense, back in control. Or maybe it would be better to put it this way: my lack of control over them ceased to be a problem.

7. The Mental Modules That Run Your Life

Page 96

Feelings aren’t just little parts of the thing you had thought of as the self; they are closer to its core; they are doing what you had thought “you” were doing: calling the shots.

Page 103

Feelings don’t just bring specific, fleeting illusions; they can usher in a whole mind-set and so alter for some time a range of perceptions and proclivities, for better or worse.

Page 104

If the way they seize control of the show is through feelings, it stands to reason that one way to change the show is to change the role feelings play in everyday life.

8. How Thoughts Think Themselves

Page 105

Zen is for poets, Tibetan is for artists, and Vipassana is for psychologists.

Page 111

thoughts, which we normally think of as emanating from the conscious self, are actually directed toward what we think of as the conscious self, after which we embrace the thoughts as belonging to that self.

Page 115

And I don’t mean just focus on whatever thought is distracting you — I mean see if you can detect some feeling that is linked to the thought that is distracting you.

9. “Self” Control

Page 135

The more you do that, the less the urge seems a part of you; you’ve exploited the basic irony of mindfulness meditation: getting close enough to feelings to take a good look at them winds up giving you a kind of critical distance from them. Their grip on you loosens; if it loosens enough, they’re no longer a part of you.

Page 135

RAIN. First you Recognize the feeling. Then you Accept the feeling (rather than try to drive it away). Then you Investigate the feeling and its relationship to your body. Finally, the N stands for Nonidentification, or, equivalently, Nonattachment.

10. Encounters with the Formless

Page 143

As you ponder these words—formlessness and emptiness—two other words may come to mind: crazy and depressing.

Page 144

There is a pretty uncontroversial sense in which, when we apprehend the world out there, we’re not really apprehending the world out there but rather are “constructing” it.

11. The Upside of Emptiness

Page 166

But you could look at it the other way around. Given that our experience of a bottle of wine can be influenced by slapping a fake label on it, you might say that, actually, there is a superficiality to our pleasure, and that a deeper pleasure would come if we could somehow taste the wine itself, unencumbered by beliefs about it that may or may not be true. That is closer to the Buddhist view of the matter.

Page 169

And maybe this helps explain how Weber could say that “emptiness” is actually “full”: sometimes not seeing essence lets you get drawn into the richness of things.

12. A Weedless World

Page 176

For example, it’s common to think of criminals and clergy as being two fundamentally different kinds of people. But Ross and fellow psychologist Richard Nisbett have suggested that we rethink this intuition. As they put it: “Clerics and criminals rarely face an identical or equivalent set of situational challenges. Rather, they place themselves, and are placed by others, in situations that differ precisely in ways that induce clergy to look, act, feel, and think rather consistently like clergy and that induce criminals to look, act, feel, and think like criminals.”

Page 185

There is a meditative technique specifically designed to blur this line. It is called loving-kindness meditation, or, to use the ancient Pali word for loving-kindness, metta meditation.

14. Nirvana in a Nutshell

Page 219

These two senses of liberation are reflected in the Buddhist idea that there are two kinds of nirvana. As soon as you are liberated in the here and now, you enter a nirvana you can enjoy for the rest of your life. Then, after death — which will be your final death, now that you’re liberated from the cycle of rebirth — a second kind of nirvana will apply.

15. Is Enlightenment Enlightening?

Page 232

The experience of emptiness, like the experience of not-self, defies and denies natural selection’s nonsensical assertion that each of us is more important than the rest of us.

Page 232

Emptiness, you may recall, is, roughly speaking, the idea that things don’t have essence. And the perception of essence seems to revolve, however subtly, around feelings; the essence of anything is shaped by the feeling it evokes. It is when things don’t evoke much in the way of feelings—when our normal affective reaction to things is subdued—that we see these things as “empty” or “formless.”

Page 236

What happens to essence when we let go of our particular perspective—the perspective that the feelings that shape the perceived essences of things were designed to serve?

I think the answer is that essence disappears.

Page 238

That’s the thing about feelings, a thing that is particularly true when we talk about their role in shaping essence: they can render judgment so subtly that we don’t realize that it’s the feelings that are rendering the judgment; we think the judgment is objective.

16. Meditation and the Unseen Order

Page 252

And here is an interesting feature of a calm mind: if some issue in my life bubbles up, I’m likely to conceive of it with uncharacteristic wisdom.

Page 254

It isn’t just that you feel a little more relaxed by the end of a meditation session; it’s that you observe your anxiety, or your fear, or your hatred, or whatever, so mindfully that for a moment you see it as not being part of you.

Page 264

In case all this sounds too abstractly philosophical, let me try to put it in more practical form, as the answer to this oft-asked question: Will meditation make me happier? And, if so, how much happier?

Well, in my case—and, as you will recall, I’m a particularly hard case—the answer is yes, it’s made me a little happier. That’s good, because I’m in favor of happiness, especially my own. At the same time, the argument I’d make to people about why they should meditate is less about the quantity of happiness than about the quality of the happiness. The happiness I now have involves, on balance, a truer view of the world than the happiness I had before. And a boost in happiness that rests on truth, I would argue, is better than a boost in happiness that doesn’t—not just because things that rest on truth have a more secure footing than things that don’t, but because, as it happens, acting in accordance with this truth means behaving better toward your fellow beings.

Page 264

This is a happiness that is based on a multifaceted clarity—on a truer view of the world, a truer view of other people, a truer view of yourself, and, I believe, a closer approximation to moral truth. It is this fortunate convergence of happiness, truth, and goodness that is embedded in the word dharma

Fun book club meeting tonight discussing How to Live: Or A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer. 📚

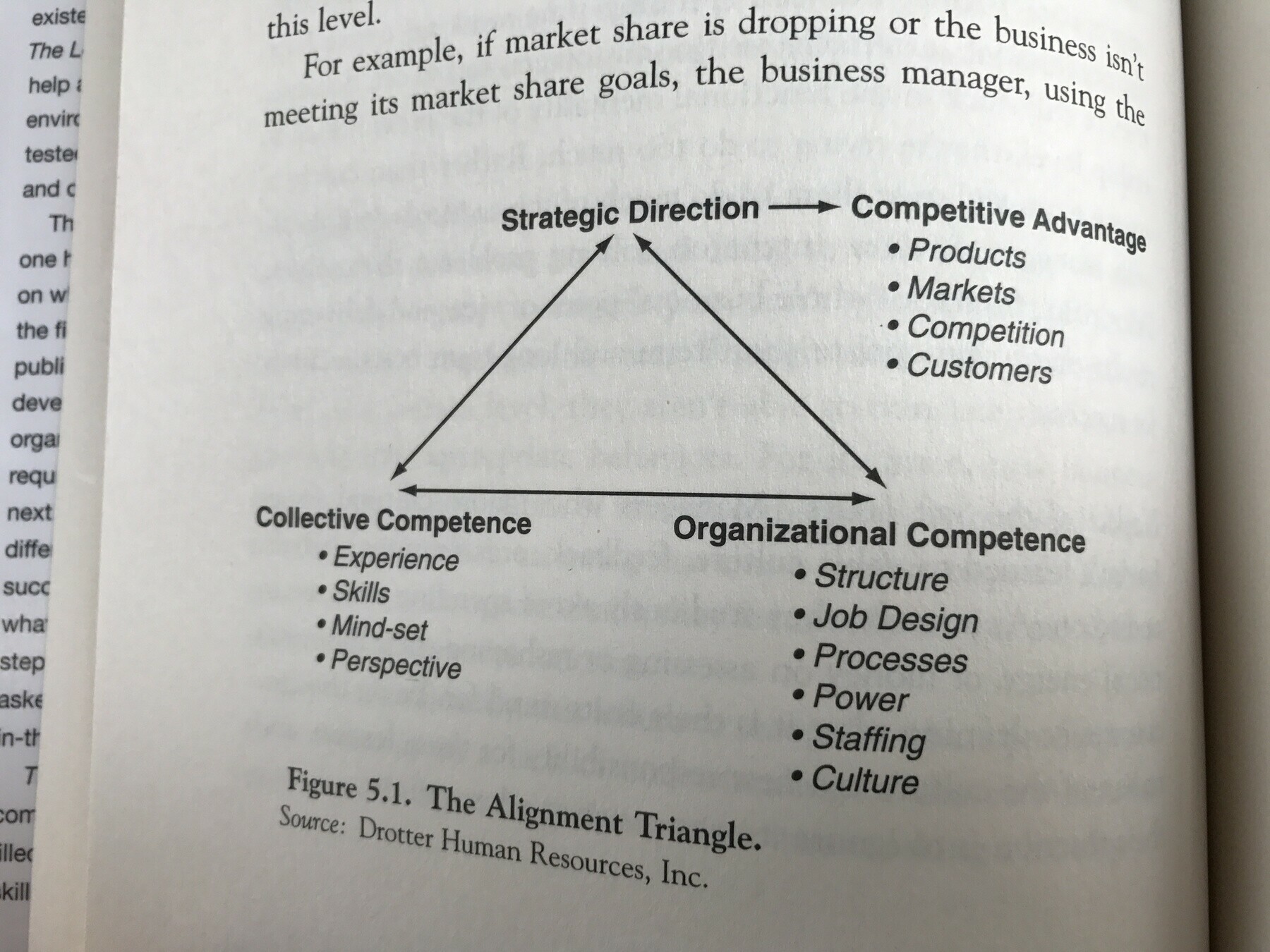

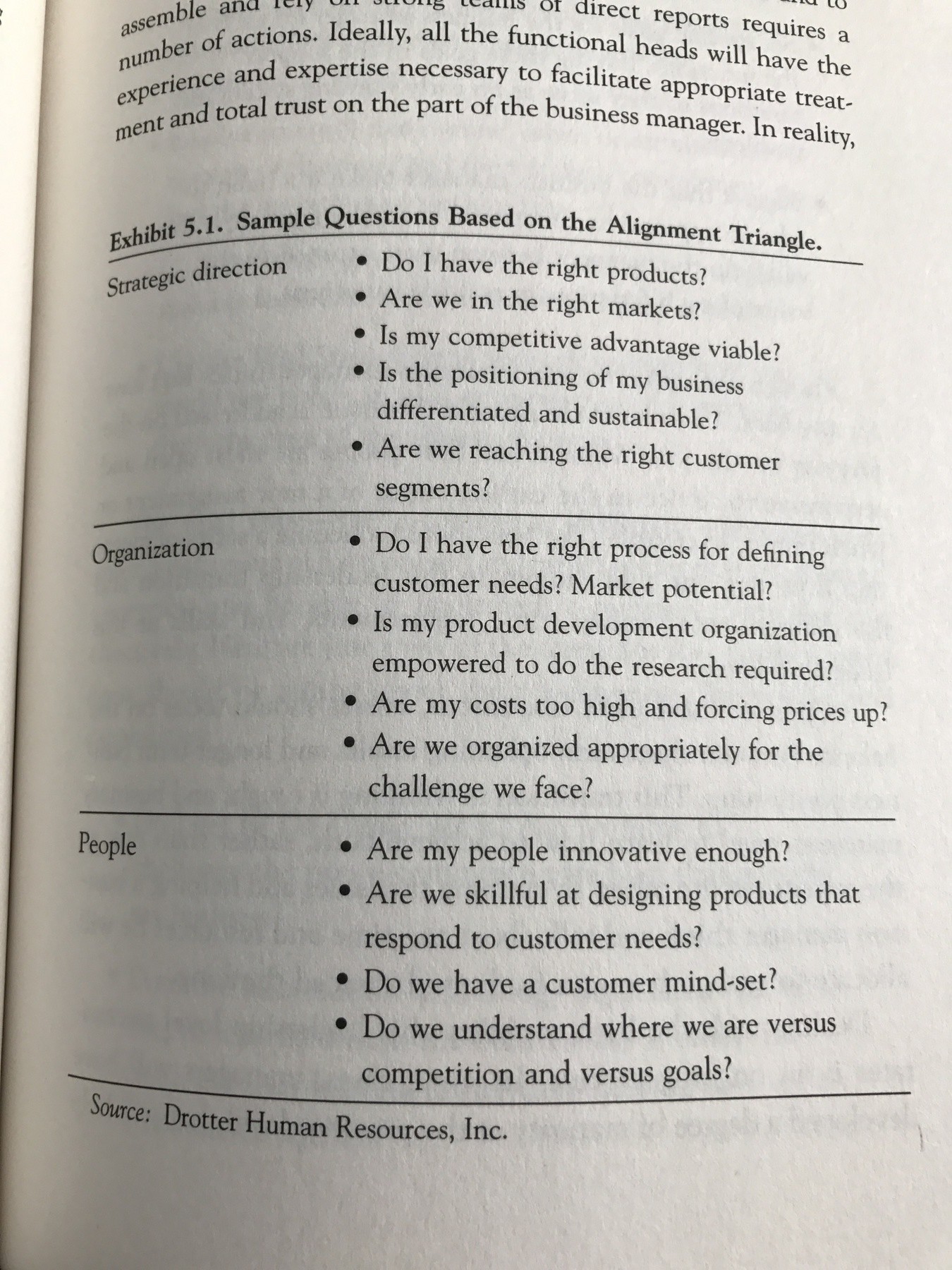

Leadership Pipeline

Notable how many references there are to “reviewing calendar” and looking at where time is spent. This is used repeatedly as a tool to assess if someone is focusing on the right work.

Alignment triangle seems like a good concept for reviewing the health of your business and the organization.

Enjoying Hillbilly Elegy by J. D. Vance. Recommended.

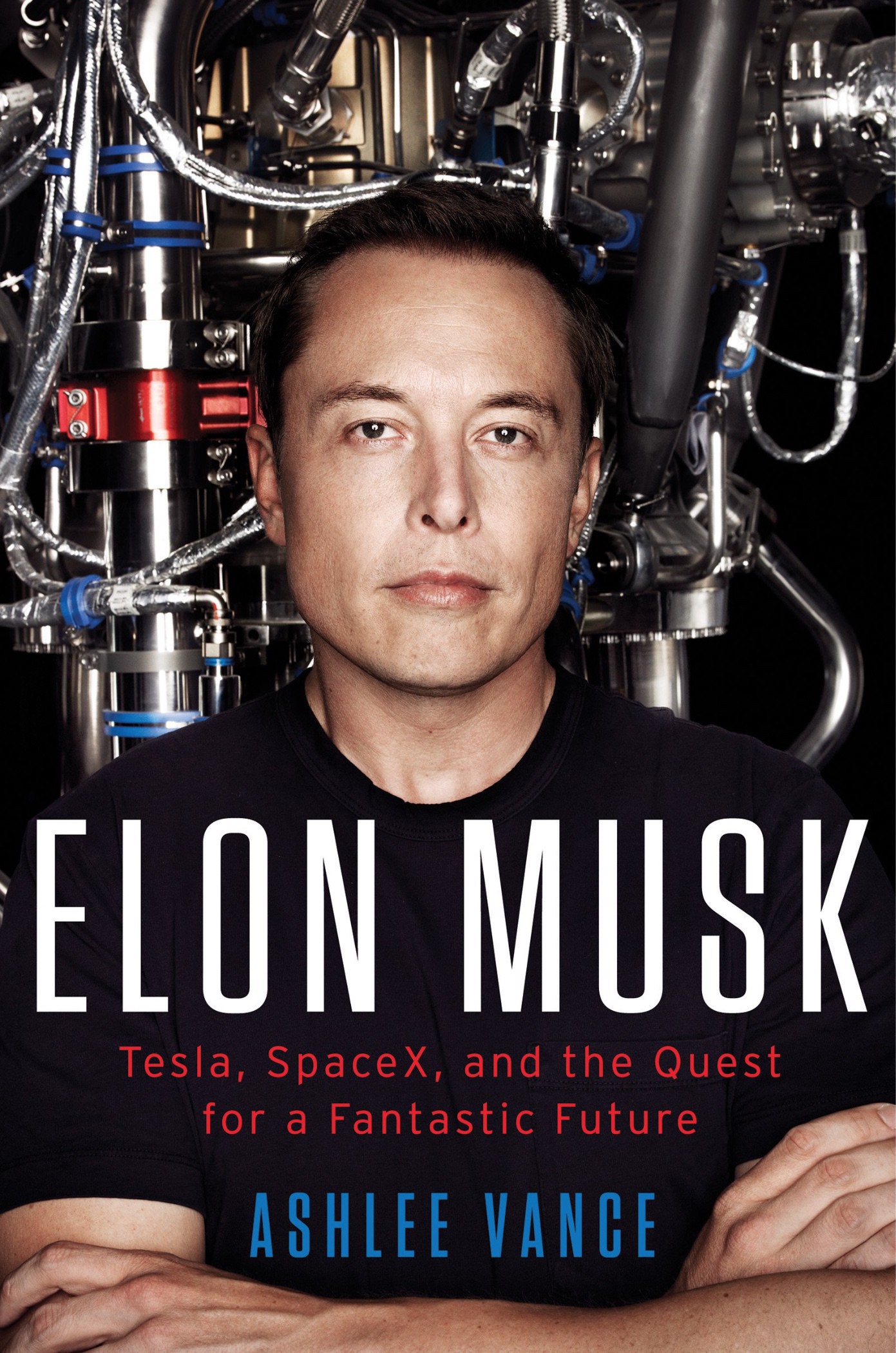

Book: Elon Musk

Enjoyed reading Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future by Ashlee Vance.

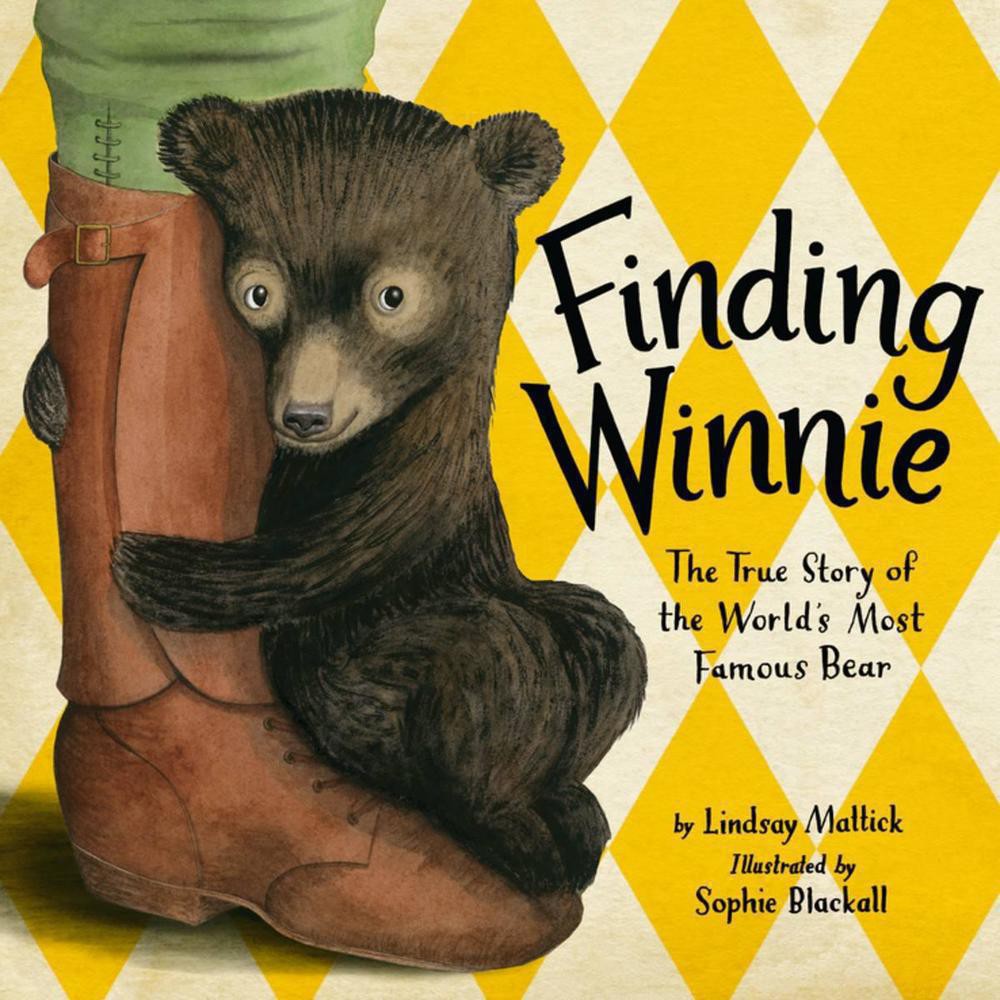

Kids Book: Finding Winnie

Tyler got Finding Winnie for Christmas this year and it’s a really awesome book. If your kid has any affinity to Winnie-the-Pooh they will love this book. Even if they don’t, it’s still a great book. Really well done and one of the better books for a bedtime story. Recommended!

Pre-ordered 3 copies of this.

Friend of @mesosphere and @ApacheMesos just published his Mesos book. Get it now! https://t.co/TTSJsmDlhL

— Matt Trifiro (@mtrifiro) December 15, 2015

Excited to read This Machine Kills Secrets, my book club pick this month.

Travels to Iceland

My friend Dennys Bisogno just self-published a photo book on a trip that he and my other friend Steve LeVahn took to Iceland. It’s a free book in iTunes. Download it and take a look! Wonderful photos and a great virtual trip to Iceland await you. The book is called “My Travels to Iceland”.

I hope to join them on a future trip to Iceland, hopefully with our other friend Layne Kennedy as well!

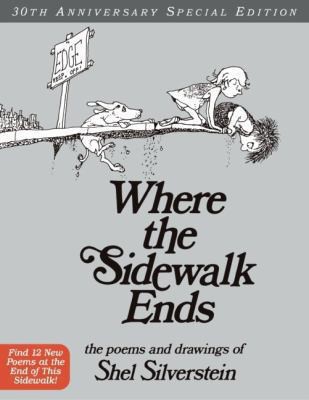

Where the Sidewalk Ends

Last night Mazie and I finished reading Where the Sidewalk Ends by Shel Silverstein. I really enjoyed reading each and every poem to Mazie, and she thought they were funny, goofy and good.

I distinctly remember reading Where the Sidewalk Ends when I was a kid. They were likely the first poems I read. I even remembered some of them. Mostly I remembered having the book and the cover of it.

We were reading the 30th Anniversary edition so I was at the youngest 9 when I read it. It was a real treat to read it to my daughter and hope that she has the same recollection when she reads it 30 years from now.

4 of 5 stars to Traffic by Tom Vanderbilt.

Money-Driven Medicine

My book club meeting tonight was just awesome. Highly recommend people read the book Money-Driven Medicine. Great discussion.

Just finished reading Traffic. Really enjoyed it.

The Soul of a New Machine by Tracy Kidder

A while back at one of my book club meetings John Riedl mentioned the author Tracy Kidder. I expressed my ignorance and he was dumbfounded. “You haven’t read Kidder? Soul of a New Machine? You have to read it.” His conviction was strong enough that I figured I needed to read it and rectify this horrific literary gap. I finished it today, and really enjoyed the book.

To start with, Soul of a New Machine is not a technical book. You do not need to know anything about computers to read this book. Also, this book was originally published in 1981. This is a time when “super-minis” were just coming out and the computer industry was jumping to 32-bit architectures. This is four years before the introduction of the first Macintosh computer. I would recommend this book to my technical friends for the same reason I would recommend Steven Levy’s Hackers (1984), Cliff Stoll’s The Cuckoo’s Egg (1990) or Out of the Inner Circle (1984). There is a great depth of history and culture in this book that is worthwhile and reminds us of the roots of our profession. We still see these roots playing out today in nearly all computer related industries. Thirty years ago it was displayed by wire-wrapping boards to make CPU’s, today it’s shown in mashups. The world of programming and computer engineering, despite what many might think, is filled with passion and creativity.

Soul of a New Machine chronicles the development of a new 32-bit computer from Data General called the Eagle (or the Data General Eclipse MV/8000). Kidder does an excellent job of telling a compelling story of how this machine comes to life and dives into the stories of the people that make it. He concludes that a computer isn’t just a machine, but represents the ideas and personalities of those that create it. He’s spot on.

Kidder illuminates the culture that has filled computer labs, computer science departments, technology, and now Internet startups for years. A born-desire to solve the unsolvable. The unstoppable desire to know how something works.

As I read Soul of a New Machine I could draw parallels to products that I had worked on in a variety of different roles. It was amusing to see that while almost all the tools have changed, so much of the “how” and the “why” has stayed the same.